Explore the Michelangelo’s genius as a sculptor in his masterpieces and philosophy, all the way through how he transformed marble into eternal art. He challenged the Renaissance norms by setting up new standards for artistic creation.

It was in 1496 that this young Michelangelo Buonarroti arrived in Rome; it was the city which pulsed with artistic and scholastic ambition. At just 21 years of age, he carried the burden of being hailed as a prodigy. This genius as a sculptor of Michelangelo cannot at all be conceived as some sort of overnight phenomenon but as the result of unrelenting, intensive work for absolute perfection. His journey through masterpieces like “David” and “Pietà” opened up our window toward not only artistic beauty but the depths of the human condition itself.

The Roman landscape of his times had more resemblance to a melting pot of great aspirations and competing egos. Michelangelo, coming fresh from Florence, brought to the fore a vision unlike any other. The Renaissance had reached its peak, and artists were now turned from artisans to creative geniuses in the truest sense of the word, almost rivaling the divine in the ability to mold and form the world. In such an energized. atmosphere, there also grew Michelangelo’s talents as a sculptor, along with the usual obstacles and calamities that came along with it.

Table of Contents

Michelangelo’s Genius as a Sculptor: The Awakening of a Sculptor

In order to really get a good sense of Michelangelo’s genius in sculpting, one must look way beyond the finished works and into the awakening of his artistic soul. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Michelangelo was not drawn to the attraction of paint nor the details of “frescoes”, but instead, his hands yearned for marble. He once famously declared:

“The sculptor’s hand is the only force that can break the spell and awaken the figures resting in the stone.”

This almost mystical belief-that the form already existed within the stone, waiting to be liberated-is a key to understanding, is central to understanding Michelangelo’s genius as a sculptor. But before he could set David free from a block of flawed marble, he had to navigate a world filled with harsh critics, rival artists, and the whims of demanding powerful patrons.

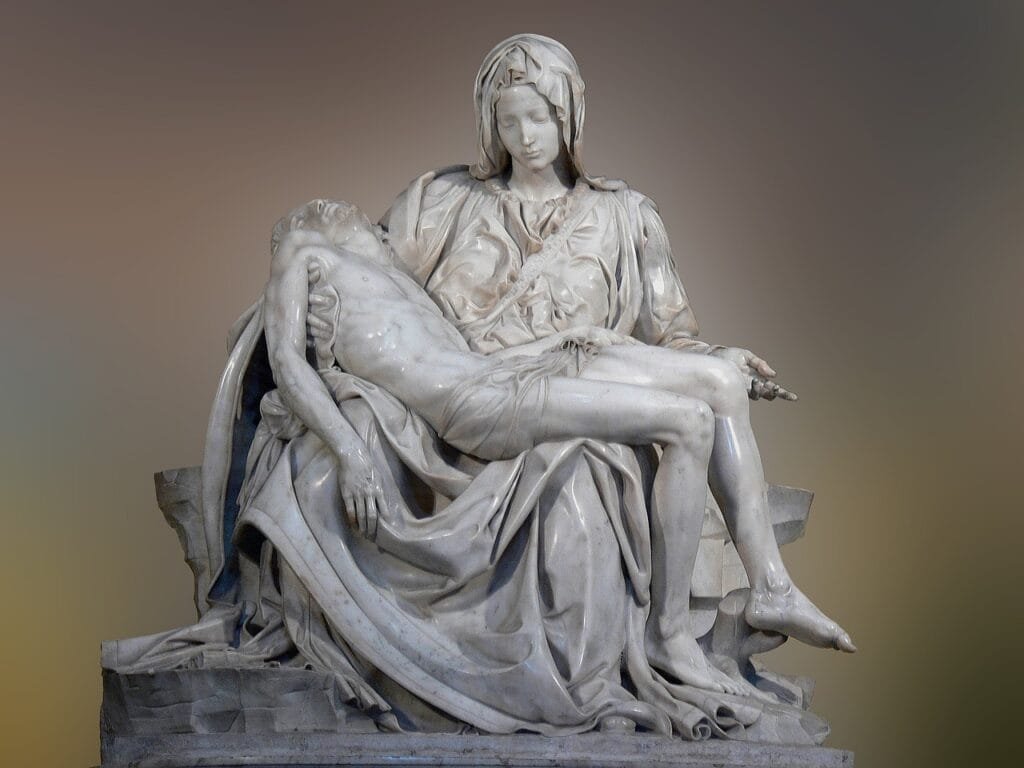

Michelangelo’s first important work was the creation of the Pietà, when he was 24 years old. In the work, Mary is depicted holding the lifeless body of Christ, an image so full of beauty and sorrow it seems as if the marble is crying, too. As his work was unveiled, many of the Romans didn’t believe that such a work could be the hand of such a young artist. Michelangelo’s answer to that was Across Mary’s sash, he quietly carved his name, a signature that sounds both pride and quiet defiance.

The Tragedy of Genius

Genius too often produces a shadow – tragedy. Michelangelo was never one to indulge in fame or in wealth. His brilliance became his burden. Each creation served only to remind him of the perfection he felt he could not quite attain.

He fought endlessly, as if he were locked in a constant fight for control over his chisel with divine forces. Even his masterpiece, David, reflects the internal battle. Carved from a flawed piece of marble, it stands as testament to his extraordinary ability to see beauty in imperfection, to reveal greatness where others saw only limitations.

David: From Flaw to Flawlessness

No better story speaks to the genius of Michelangelo’s genius as a sculptor than that of David, the biblical hero “who felled Goliath”. The commission itself wasn’t particularly unique; after all, many other sculptors had already tried to carve a statue from the poor block of marble given to Michelangelo. It sat inactive for more than 40 years, full of imperfections and fractures, useless, so many assumed before Michelangelo’s time.

Where others were searching for a lost cause, Michelangelo could see potential in that stone beneath his chisel to be given life. After two years of heavy labor, he unveiled the David we see before us-as stately, tranquil, and strong as he stands there, ready for battle rather than rejoicing. over the victory itself; muscles tense, frozen in anticipation in a fixed stare and radiating the quality of elegance – the Renaissance ideal of effortless grace.

Even contemporaries were rejoicing over David, whereas critics criticized Michelangelo over it. Some complained that it was too perfect and had no signs of vulnerability. Others said it was scandalous nudity, arrogance. Nevertheless, Michelangelo’s David survived; it stands as the ultimate symbol of the Renaissance style in art and sculpture, proof of unmatched genius.

Michelangelo’s Genius as a Sculptor: Critiques and Rivalries

Drama was aplenty in the Renaissance scene. The popular rivalry between Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci was subtle, nevertheless known to the public. The rival masterpieces were two commissions to paint murals in Florence’s Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci each thought the other a worthy opponent. He often mocked at Leonardo’s soft lines while Leonardo was said to declare the overdeveloped musculature of the figures by Michelangelo.

Perhaps the most moving criticism, however, came not from his fellow artists but from Michelangelo himself. While alive, he never was content with anything he could complete. His unfinished works are known as the Prisoners or Slaves, and they haunt like a living memory of his inner conflict. These figures, half-carved, seem to come out of raw marble as if they themselves could not be delivered fully from their marble prison even by him.

Michelangelo’s Genius as a Sculptor: Philosophy of Creation

The very essence of the philosophy of Michelangelo was the believe in the fact that art is a divine act and one has to show God’s handiwork. He considered himself not to be any ordinary artist but the channelling god’s perfection is going to act through him. He said,

“Every block of stone has a statue inside it and it is the task of the sculptor to discover it.”

This explains the notion that creation did not represent an activity of making something anew but rather an action that lay out for everyone to see something eternally existing.

Michelangelo’s Genius as a Sculptor: The Legacy of Michelangelo

He lived on to the age of 88, which is extraordinary in that time. Even in his final days, he was pushing what one could consider architecturally possible. As one considers Michelangelo’s genius as a sculptor, it becomes apparent that his best piece wasn’t any specific sculpture or edifice but the idea that greatness resides in every block of stone-in every human soul-waiting to be unearthed.

And so, Michelangelo’s genius as a sculptor inspires not only artists but thinkers up to the present times to remind oneself that best artistry is not only about beauty but could also have something to do with discovering the potential existing in the raw materials of our world and of ourselves.

Share your favorite Michelangelo masterpiece or how his genius as a sculptor inspires you in the comments below!

Read this post to explore Benjamin Franklin’s 13 virtues, a timeless guide to personal development and ethical living.